Table of Contents

Typing a URL is pure muscle memory.

Click the address bar, type a name, hit Enter. A page appears almost instantly.

But in that single second, a massive engineering marathon unfolds. Your browser, operating system, and servers across the globe coordinate networking, security, and rendering with astonishing precision.

Whether you’re a developer or simply curious, let’s walk through what actually happens when you press Enter.

Phase 1: Understanding What You Typed

The browser doesn’t blindly send text into the internet. The first thing it does is interpret your intent.

Is it a URL or a Search?

Modern address bars, often called omniboxes, must decide:

- Are you entering a web address like

example.com? - Or are you searching for “best pizza near me”?

This decision determines whether the browser initiates a network request or hands the query to a search engine.

Defaulting to Security: HTTPS and HSTS

In the past, browsers defaulted to insecure HTTP. Today, security standards have flipped that behavior.

Many sites are on the HSTS Preload List, a hardcoded list in browsers that enforces HTTPS. If a site is on this list, the browser never attempts to use HTTP, eliminating downgrade attacks.

Browsers are moving toward a future where HTTPS is the default for all public websites.

Supporting Global Domains: Punycode

The internet was initially designed to support only Latin characters. To support international domains, browsers use Punycode, which converts Unicode characters into ASCII-safe representations.

Example:

öbb.atbecomesxn--bb-eka.at

This system enables global access but introduces risks. Attackers can exploit lookalike characters across different character sets to create phishing URLs. Modern browsers actively detect and block these “homograph” attacks.

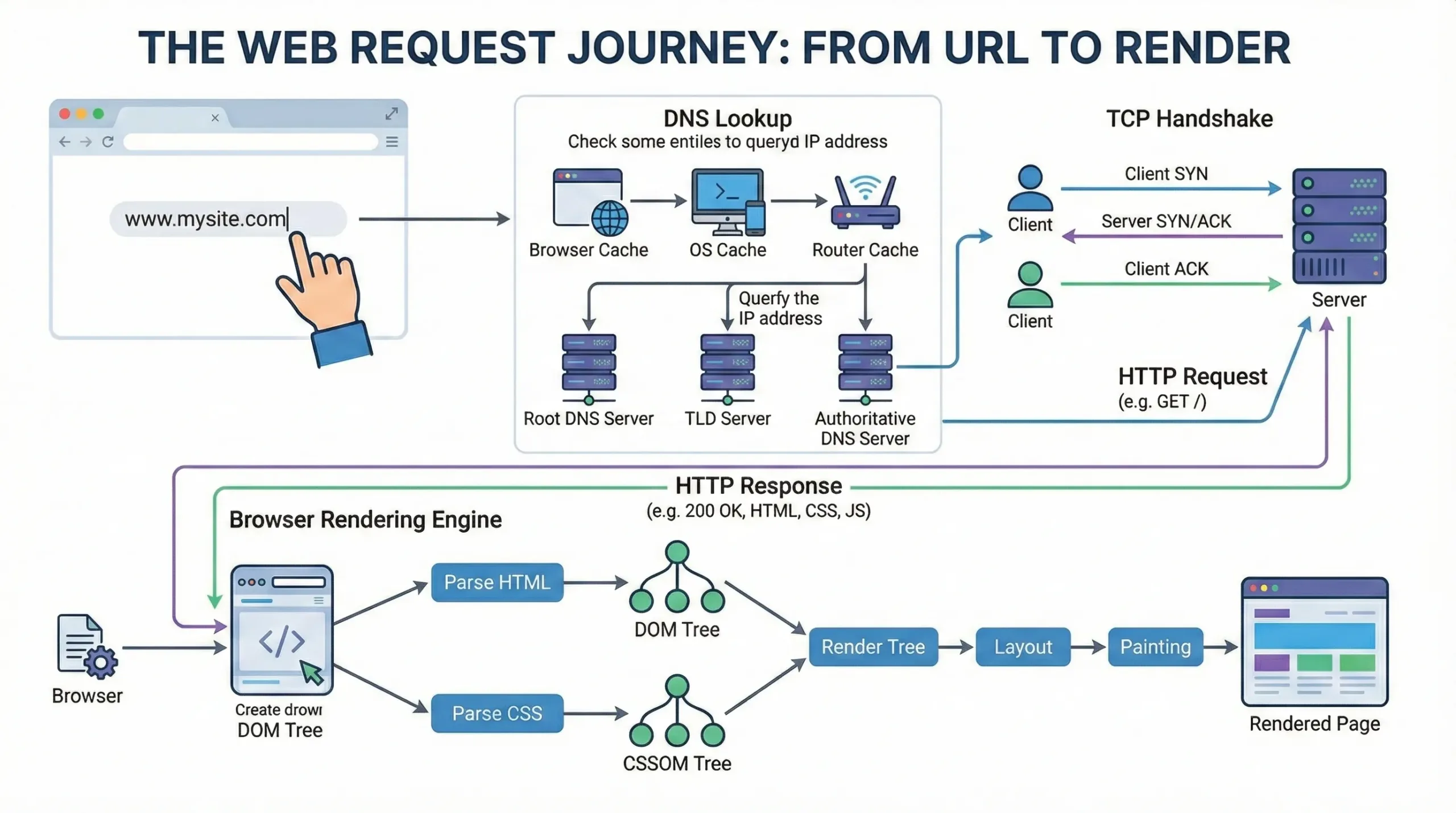

Phase 2: Finding the Server (DNS Resolution)

Your browser knows who you want to visit, but not where they are. It needs an IP address.

Checking Caches First

To avoid unnecessary work, the browser checks:

- Its own DNS cache

- The operating system cache

If the IP address is already known, the browser can skip the rest of this phase entirely.

Asking the Internet

If there’s no cached answer, the request goes to a DNS resolver, often provided by your ISP or a public service like 1.1.1.1.

The resolver follows a hierarchy:

- Root DNS servers

- Top-Level Domain servers (

.com,.org, etc.) - Authoritative name servers

Only the final server knows the exact IP address for the domain.

Privacy Upgrade: Encrypted DNS

Traditional DNS lookups were unencrypted, meaning anyone on the network could see which sites you visited. Modern browsers increasingly use DNS over HTTPS (DoH) or DNS over TLS (DoT) to encrypt these lookups and protect user privacy.

Phase 3: Establishing a Secure Connection

Now that the browser has an IP address, it needs a reliable and secure connection.

The TCP Handshake

The browser and server perform a three-step exchange:

- SYN

- SYN-ACK

- ACK

This ensures both sides are ready to communicate and that data will arrive in the correct order.

The TLS Handshake

Next comes encryption. The TLS handshake establishes secure keys so data can’t be read or modified in transit. With TLS 1.3, this process is faster than ever, often completing in a single round trip.

The Shift to HTTP/3 and QUIC

While most web traffic still runs on TCP, HTTP/3 is gaining traction. It runs on QUIC, which is built on UDP.

Why this matters:

- TCP blocks all traffic when a single packet is lost.

- QUIC supports independent streams, so a lost packet doesn’t stall the rest.

This is especially beneficial on mobile devices and in unstable network conditions.

Phase 4: Requesting and Receiving Data

With the connection established, the browser sends an HTTP GET request to retrieve the page.

Time to First Byte (TTFB)

The clock starts ticking when the request is sent. The time from when the browser requests a resource to when it receives the first byte of data is called TTFB. Well-optimised sites aim to keep this under a second.

Reverse Proxies and Load Balancers

Your request rarely hits the application server directly. It often passes through:

- Reverse proxies

- Load balancers

- CDN layers

These systems distribute traffic, cache responses, and block malicious requests before they reach the core application.

103 Early Hints

Some servers send a 103 Early Hints response while generating the final HTML. This allows the browser to start downloading CSS or fonts early, making better use of server processing time.

Phase 5: Parsing the Page Structure

The server sends the response in small chunks, and the browser starts working immediately.

HTML Parsing

Raw bytes are converted into characters, then tokens, and finally into nodes that form the DOM (Document Object Model).

The Preload Scanner

In parallel, a background scanner scans the HTML for external resources such as stylesheets, scripts, and images. It starts fetching them early to avoid delays later.

JavaScript and Blocking

JavaScript can pause HTML parsing unless it’s marked with async or defer. This is why unoptimized scripts can delay page rendering and why script placement matters.

Phase 6: Rendering and Painting

Now the browser turns data into pixels.

Building the Trees

- DOM defines structure

- CSSOM defines styles

These combine into the Render Tree, which includes only visible elements.

Layout (Reflow)

The browser calculates the exact positions and sizes of every element relative to the viewport. This step is computationally expensive and triggered again on resize or significant DOM changes.

Paint and Composite

The browser paints colors, text, borders, and images onto layers. These layers are then composited, often using the GPU, to produce smooth scrolling and animations.

Every URL you type triggers thousands of precise decisions across the internet. Once you see the process, you never look at “loading” the same way again.

Leave a Reply